Tokyo District Court Says All System Components Must Be In Japan for Accused Video Distribution System to Infringe Japanese Patent

In March 2022, the Tokyo District Court applied the principle of territorial jurisdiction to dismiss a patent infringement claim of Dwango Co., Ltd. against American company FC2’s video distribution system. According to the decision, there is no infringement of the patent’s system claims because FC2’s servers are located in the United States, even though the users instruct the system from Japan, and receive video distribution services on terminals located in Japan. Japanese and American patent law appear to dictate opposite results in similar circumstances.

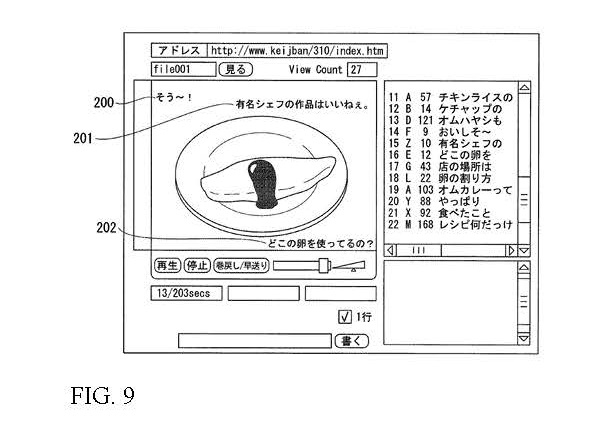

Dwango Co., Ltd. (“Dwango”) filed a patent infringement lawsuit in the Tokyo District Court (“TDC”) against FC2, Inc. (“FC2”) in 2019, alleging that FC2 infringed Dwango’s Japanese Patent No. 6526304. Dwango’s patent is directed to the comment delivery system portion of Dwango’s “Nico Nico Douga (Smile Videos)” video distribution service.

On March 24, 2022, the Tokyo District Court dismissed Dwango’s claim, explaining that even though FC2’s system falls within the technical scope of the patent’s system claims, FC2’s comment distribution system is partially implemented abroad, namely, in the United States, and thus it cannot be said that Dwango’s patent is being “produced” in Japan.[1] Due to the significant rise in video distribution services, there has been ongoing debate as to whether infringement is established in such a case, and the Dwango decision has now become a “hot topic” in Japan’s intellectual property law community.

The TDC’s Dwango decision is especially noteworthy because it appears to dictate the opposite result of a “mirror image” case filed in the United States in similar circumstances.

Accused infringer FC2 is a U.S. corporation established by a Japanese founder. FC2 also provides a video distribution service having a feature that allows users to send and receive comments while viewing videos. FC2 video servers and comment system servers are located in the United States, while the terminals and users are in Japan.

Dwango argued that FC2’s system falls within the technical scope of Dwango’s patent, and the TDC agreed. Dwango also argued that FC2’s transmitting of the video and comment files from FC2’s U.S. servers to the Japanese users’ terminals constitutes “production” of the patented system and therefore infringes Dwango’s Japanese patent. The Tokyo District Court disagreed, ruling that transmitting of video and comment files by FC2’s server in the United States does not qualify as “production” of Dwango’s system in Japan.

This TDC decision was made based on the “principle of territorial jurisdiction,” which means that the Japanese patent right is only effective in the territory of the country where the patent was granted; i.e., Japan. The Tokyo District Court stated that, to satisfy the “work” requirement for infringement of a Japanese patent, the product including all the limitations of the patent claim should be newly created in Japan.

Dwango argued that a decision of non-infringement on the basis explained by the court would be extremely unreasonable because most components of FC2’s system are located in Japan and FC2’s actions as a whole can be considered to be performed within Japan, although FC2’s server is located in the United States. However, the TDC explained that whether FC2’s actions constitute “production” of the patent should not be determined based on the fact that most components of FC2’s system are located in Japan.

Furthermore, the court stated that, in this particular case, there is no reason to suspect that FC2 intentionally installed their server in the U.S. merely in order to avoid liability for patent infringement. The Dwango case produced the opposite result that would be obtained in the United States under similar circumstances.

In the well-known Research In Motion decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”), the famous Blackberry system of Research In Motion (“RIM”) was found to infringe the system claims of NTP, Inc.’s (“NTP”) U.S. patent even though RIM’s servers were located in Canada, outside the territorial effect of the patent.[1] NTP had filed a lawsuit against RIM for infringement of NTP’s email system patent (U.S. Patent No. 5,436,960).

NTP’s patented system integrates an existing electronic mail system with a radio frequency (“RF”) wireless network to enable mobile users to receive emails over the wireless network. RIM provided the accused infringing “BlackBerry” system that was ubiquitous in the early 2000s. RIM’s system sent existing emails created by U.S. users on handheld “BlackBerry” devices connected to U.S. RF wireless networks to a mail server, forwarded the emails to a delivery server located in Canada, and further forwarded the emails back to the users’ handheld devices located in the U.S., over the U.S. based wireless network.

The CAFC decided that the location of “use” of the Blackberry system is the United States because the place where the system is controlled and where the benefits from the system are obtained is the United States, even if some components of the system are located outside the U.S., i.e., in Canada. Thus, the CAFC concluded that direct infringement was established under 35 U.S.C. Section 271(a) of the U.S. Patent Law. In reaching its decision, the CAFC relied on a 1976 decision of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals which held that implementation of a U.S. Government navigation system constituted “use,” i.e., infringement, of a patented system where the navigation system was controlled from within the U.S. even though the radio stations of the system were located in Norway.[2]It is important to note that, on the other hand, as to the corresponding method claims of NTP’s electronic mail system, the CAFC noted that “a process cannot be used ‘within’ the United States as required by section 271(a) unless each of the steps was performed within this country.” In other words, the outcome of the Research In Motion case would have been the same as in the Tokyo District Court’s Dwango case, had NTP asserted infringement of only the method claims of its email system patent.Since implementation of IT technology is not limited by location, legitimate protection of patented IT technology is seen to be limited by the traditional Japanese “principle of territorial jurisdiction.”

For example, if Japanese law states that a patent is not infringed because some components of the patented system are located and/or controlled abroad, it becomes possible to avoid infringement by intentionally installing the server outside the country. Even if this was done, it would be very difficult to prove that such foreign location of the server was done “only” to avoid infringement liability in Japan. To effectively enforce the patent in Japan, it will be necessary for the Tokyo District Court to reconsider the location from where the system is controlled (i.e., from within Japan) and where the benefits are obtained (also in Japan), in determining IT patent infringement, as the CAFC did in the Research In Motion case.

[1] Dwango Co., Ltd. v. FC2, Inc., Tokyo District Court, Case No. 25152 (2022).

[2] NTP, Inc. v. Research In Motion, Ltd., 418 F.3d 1282 (2005).

[3] Decca Ltd. v. United States, 210 Ct. Cl. 546, 544 F.2d 1070 (1976).